Martha Nussbaum’s Justice for Animals

In her book "Justice for Animals" philosopher Martha Nussbaum examines what the relationship between human society and other sentient beings should be and how we might get there.

Note: This post was originally published on August 28, 2024, at AmericanGaia.Me.

—

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2023. Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility. New York: Simon & Schuster.

For the pdf version of this article go here.

Imagine yourself mingling in the crowd at a local fair. In front of you half a dozen people cluster around the stand of the Audubon Society, an organization that protects birds. Gingerly you thread your way past them, when you catch a glimpse of the man who holds their attention. He balances something precious on his arm. You focus, then realize he is carrying an osprey, a brown-and-white raptor whose kind you have only ever seen from afar, soaring high above, sometimes plunging towards Earth like a missile to catch an unsuspecting fish.

And here she sits, on the arm of a human, a mere seven feet from you. Mesmerized you study the sharp beak, the powerful talons, the humorless eyes and observe just how slender and light this bird is. Why has she chosen to perch within reach of humans, who can harm her so easily? Why is she not trying to escape?

What you just experienced was wonder. Wonder, says philosopher Martha Nussbaum in her book Justice for Animals, is an important emotion, for it can make me, you, all of us, care about the welfare of non-human life forms. From this central idea she has derived powerful and wide-ranging conclusions, and I'll share with you what they are.

Here's the roadmap: We start by meeting the author and exploring her motivation for writing the book. Next I'll outline its thesis that animals should be treated as citizens with rights and connect that idea with her thoughts on our ability to wonder. We'll briefly look at three philosophical approaches of which Nussbaum is critical. Then we'll examine her own Capabilities Approach. We'll see why it protects only sentient creatures and find out what sentience is, exactly. Then we'll zoom in on practical applications, in particular: What do we owe animals we have bred to live amongst us? What do we owe animals that invade our space? Animals we eat? Animals in the wild? And lastly, what happens when our desire to respect animal rights runs up against other ethical or philosophical principles we also cherish?

Meet Martha Nussbaum

In academia it is common practice to bolster your authority with jargon and claims of objectivity. Author Martha Nussbaum, a professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago, has done the opposite. She keeps jargon to a minimum in hopes of reaching not only academics but also lay readers. And rather than feigning objectivity, she admits to having profound stakes in the matter: Her daughter Rachel had been a passionate advocate for animals - so much so that she introduced Martha to the need for animal justice years ago. In her forties Rachel died of a fatal infection. Martha poured her grief into building a philosophical system that would multiply her daughter's impact on the world. Justice for Animals is thus a memorial in book form.

I have been wondering about Rachel, the woman who inspired this work. She must have been remarkable.

The volume addresses two distinct audiences whose intellectual needs differ greatly. The first is ethically inclined lay readers - the large group people who are key to achieving the social change this book is after. The second is fellow philosophers, experts with a deep understanding of the questions the volume tackles. They want to know that Nussbaum's argument has sound roots in our (mostly European) intellectual tradition and that it can withstand criticism.

Writing to both novice and expert readers is challenging. So if you are a non-expert like myself, don't be surprised if the reading occasionally veers into the abstract. Consider it par for the course.

Let's now see what Justice for Animals has to say.

Animals are citizens

Nussbaum asks her readers for radical change: Stop, she insists, treating animals as toys, collateral damage from human living space expansion, or hamburger meat that is not yet dead. And start recognizing them as citizens - full members of society complete with rights and obligations.

It's an unsettling imperative. First, it jeopardizes the social status we humans derive from our superiority to other life forms - and if you have read my letter to Pope Francis, you'll have a sense of how important superiority to flora and fauna has been to the Christian self-image. But more tangibly, Nussbaum's demand threatens a wide range of vested business interests that rely heavily on the exploitation of animals. There are puppy mills, zoos and horse race tracks. And then there are the factory farms, which in the United States cage up ten billion animals each year. [1]

How do we know that animals have rights?

Nussbaum asserts that we humans are deeply indebted to the other animals, simply because we have so disrupted their existence.

Each sentient creature, she believes, is entitled to pursue a flourishing life without being thwarted by humans. Whenever humans prevent the flourishing of sentient beings, they commit acts of injustice, no matter if they were driven by malevolence or simply behaved negligently, and also no matter if the thwarting was caused by a single human being or by a society of millions.

We start with wonder …

You may now wonder how Nussbaum knows, or believes to know, that animals have rights. That conviction is based on humans' innate ability to wonder, for it makes us empathize with creatures who strive and recognize their right to pursue the goals inherent in their species nature.

Wonder is what you experienced when making the acquaintance of the raptor just a few minutes ago. It

"involves first being impressed by something, brought up short, and then being motivated to try to figure out what is going on behind the sights and sounds that impress us."(p. 10 - "p." stands for "page number")

As we wonder, we suspend worry about our own welfare and step into the shoes of another life form, attempting to figure out how the world looks through that being's eyes:

"We see that creatures have a purpose, that the world is meaningful to them in some ways we don't fully understand, and we are curious about that: What is the world for them? Why do they move? What are they trying to get? We interpret the movement as meaningful, and that leads us to imagine a sentient life within." (p. 11)

Wonder gets often buried under the demands of daily life: Meeting deadlines, wrangling family schedules, keeping up with social media. But as soon we slow down and allow ourselves space for exploration, it will re-emerge.

… and then experience compassion and transition anger

Wonder opens us up to compassion, which is care for the other being's thriving. This is where we recognize their right to flourish. When we then see the creature's flourishing stymied, compassion gives way to transition anger: the recognition that an injustice has been committed, coupled with the desire to prevent its recurrence. Transition anger, in turn, sparks beneficial remedial action.

To Nussbaum, any person who opens him- or herself to wonder and compassion can access the recognition that sentient animals have rights. She herself moved from compassion to the recognition that humans stymie animal flourishing consistently. Transition anger and years of training in philosophy then led her to develop this chain of ideas:

Humankind dominates just about all ecological systems on the planet.

Through their dominance humans, the world over, have profoundly and negatively altered the living conditions to which animals are adapted and on which they depend.

Thus humans have systematically impeded the flourishing of other sentient creatures.

Having impeded the flourishing of sentient beings on a planetary scale, we have a collective duty to provide relief by systematically supporting their flourishing.

Schools of thought that have examined animal justice

For intellectuals, rootedness in tradition is important. And so Nussbaum goes to great lengths examining existing philosophical approaches to animal justice, identifying their shortcomings, and making the case for her own, alternative, approach.

The community of animal rights philosophers is small. Animal Justice gives the impression that at present, it consists of fewer than a dozen intellectuals, who fall into three schools of thought: The "So Like Us" approach, the utilitarians, and the Kantians.

Let's take a brief look.

School 1: the "So Like Us" approach

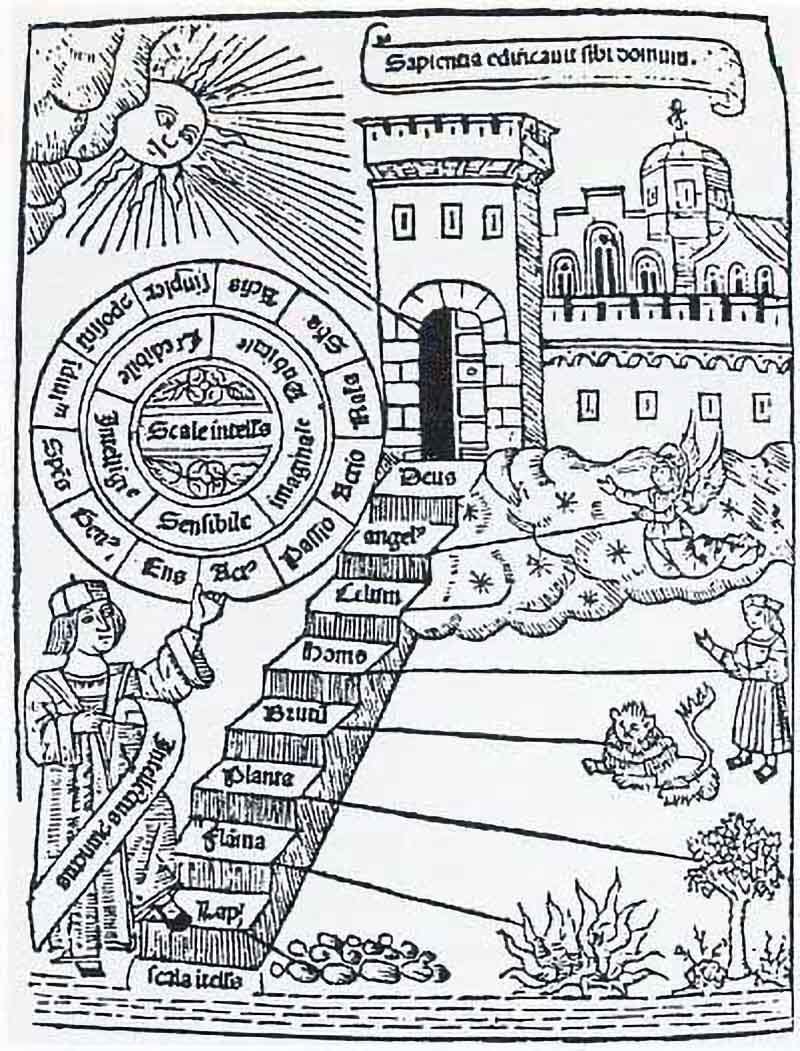

The adherents of the "So Like Us" approach typically write on the background of the "Great Chain of Being," a concept that the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy dates back to ancient Greece:

"Aristotle suggested that living things could be arranged in a graded scale, starting from plants at the bottom and ending with humans at the top. This idea was further developed in Neoplatonism, and in Medieval times, it transformed into the idea of 'the Great Chain of Being'.” (Stanford Enclyclopedia of Philosophy)

Today, says Nussbaum, the Great Chain of Being is a central Judeo-Christian idea (p. 23-24). What she does not mention is that the Christian tradition conceives the Great Chain of Being as the following hierarchy:

God

Angels

Humans

Animals

Plants

Rocks or minerals.

If you grew up in Europe or the Americas, you've likely imbibed the Great Chain of Being since childhood without ever noticing.

So assume that this concept grounds your understanding of relations between humans and non-humans. You see animals of a specific species mistreated and experience wonder, compassion, and transition anger. How might you respond to these emotions? One possibility lies in pointing out how very much that animal species resembles the human race - for example because its members can perform language tricks or count to ten or recognize themselves in a mirror. You might then propose that because this species is just like us - "human-adjacent", so to speak -, it should receive protections similar to those we humans enjoy.

Modern philosophers and legal scholars have made this sort of argument for chimpanzees and dolphins. But Nussbaum cautions that it is treacherous for two big reasons: If you believe in the stratification of all life on a fixed ladder, you may be able to elevate one or the other animal species to the human rung, but most will by the necessity of hierarchy be left behind. That, to her, constitutes strike number one against this approach. Strike two is that embracing the "So Like Us" standpoint means further legitimizing its underlying construct, the Great Chain of Being. And that, finds our author, should be abolished in its entirety, because it is flat-out wrong.

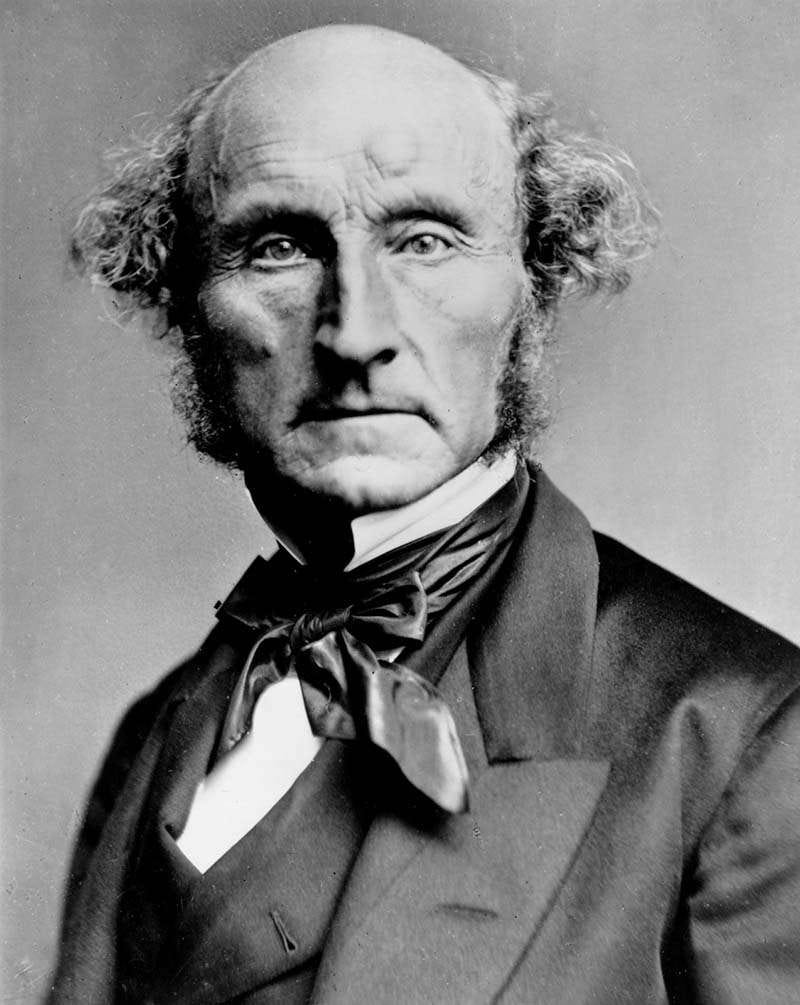

School 2: the utilitarian approach

A second approach dates back to Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. These 19th century utilitarians said that each being - and they had mostly humans in mind - seeks to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. They also believed that individual preferences could be aggregated to the societal level, that it was the government's responsibility to do so, and that the ultimate goal of social policy should be to maximize net pleasure and minimize net pain across all members of society. What's not to like about a social policy that seeks to make its subjects happy?

In the twentieth century neo-utilitarians applied this reasoning to non-human animals. But utilitarianism suffers from a number of flaws that make it hard to use. For example: It does not explain how to quantify pleasure and pain within a given individual. It also does not offer guidance on how to compare pleasure and pain among individuals, which is necessary for aggregating individual states into a just societal policy. Moreover for Nussbaum, engaging in wonder, compassion and transition anger enables us to see that each sentient being is an end in him- or herself. Utilitarianism does not see it that way. Its line of thinking permits making one individual supremely miserable if doing so will marginally increase pleasure for a hundred others. For Nussbaum, sacrificing the dignity of the individual - be that individual human or not - to the desires of the many is an injustice. This, in her view, makes utilitarianism a non-starter.

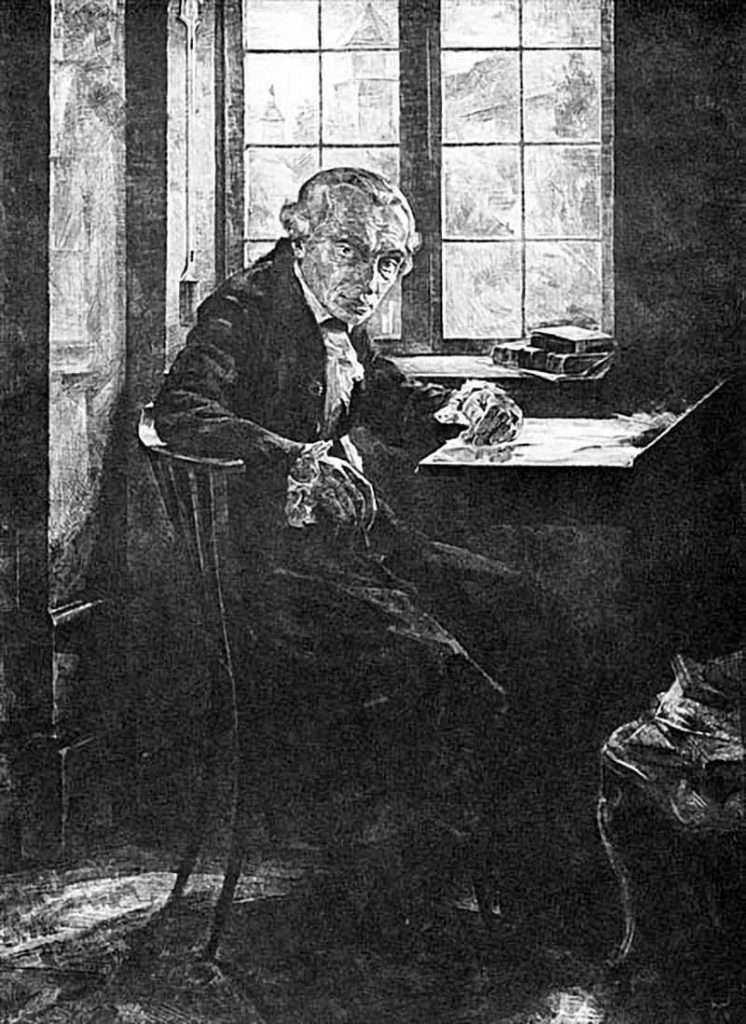

School 3: the Kantian approach

The third school of thought is closest to Nussbaum's own beliefs. Its proponents trace their origins back to German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and they believe that all individuals - again, mostly of a human kind, but one can expand this thinking to other sentient animals as well - are ends in themselves, purposes in their own right. They should never be reduced to the status of a mean, or tool.

It is therefore no surprise that Nussbaum prefers the Kantian philosophy over that of Bentham, especially as applied to animals by Kristine Korsgaard. But Korsgaard makes claims about the moral distinction between human and non-human animals that Nussbaum rejects - for example that animals do not have access to rationality, and that if animal lives have value, it is only because humans have said they do (p. 71-72). Besides, the Kantian approach offers little guidance on how sentient animals should be treated once their status as ends in themselves has been established.

This is why Nussbaum wants us to use a better philosophical framework, and, of course, she believes that she has created it. Its name is the "Capabilities Approach." The fact that it is a new, fourth, framework for thinking about animal rights makes Animal Justice a really important work.

Martha Nussbaum's Capabilities Approach

Originally the creation of development economist and Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, the Capabilities Approach maintains:

"a society is even minimally just only if it secures to each individual citizen a minimum threshold amount of a list of Central Capabilities, which are defined as substantial freedoms, or opportunities for choice and action in areas of life that people in general have reason to value. Capabilities are core entitlements, closely comparable to a list of fundamental rights." (p. 80)

The above formulation is human-centric, because it calls for substantial freedoms that people value. For humans, important capabilities include the ability to stay in good health, engage one's creativity and imagination, participate in the body politic.

But Nussbaum has expanded this approach to include sentient non-human animals. She explains that much as these differ from one another, especially across species boundaries, they all want similar capabilities, namely:

"being able to enjoy good health, to protect one's bodily integrity, to develop and enjoy the use of one's senses and imagination, the opportunity to plan a life, to have a variety of social affiliations, to play and have pleasure, to have relationships with other species and the world of nature, and to control, in key ways, one's own environment." (p. 81)

The task at hand, then, is to get to know the species in question and determine its specific needs, by asking, for example, "What does an opossum require to stay healthy?" Once that is done, we can meet these creatures' needs.

The importance of sentience

But wait a moment. There are 2.13 million described animal species on the planet, which are divided into over 1 million species of insects, 11,000 birds, 11,000 reptiles, and 6,000 mammals. Are we supposed to manage the needs of all of them?

No, says Nussbaum, and this is where the quality of sentience becomes important: If a species meets this criterion, its individual members are entitled to protections under the Capabilities Approach. If not, the Capabilities Approach does not apply to them.

So what is sentience? In the study of animal behavior, it is commonly understood as awareness of self. More specifically, it is

"a multidimensional subjective phenomenon that refers to the depth of awareness an individual possesses about himself or herself and others." (L. Marino, in Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, 2010)

Justice for Animals says sentience consists of three dimensions: nociception, subjective awareness, and a sense of salience. Let's explain.

Sentience dimension 1: nociception

Dimension number 1, nociception, is the ability to recognize noxious stimuli as dangerous or bad. This usually happens through pain receptors and nerves that transmit damaging stimuli to the brain. For example, when I touch a hot stove, I feel a jolt of pain. While scientists usually limit themselves to this negative definition, Nussbaum prefers one that is broader. To her, nociception means both recognizing the noxious as bad and discerning the beneficial as good.

Sentience dimension 2: subjective awareness

Dimension number 2, subjective awareness, is the possession of a point of view on the world. I understand this as a confluence of sensory inputs or experiences and their aggregation, through memory, into the experience of an "I" or "Me" that is different from what is not "I" or "Me" and that acquires its own history. Here are some examples of experiences that have become building blocks of a fictional character's personal history:

As a child I despised stuffed peppers. Today I love them.

I graduated from law school and then spent a decade serving as an assistant district attorney.

I lived abroad for several years, returning only last year.

Yesterday I went to church, where I ran into several friends.

Sentience dimension 3: a sense of salience

Dimension number 3 is a sense of salience. That's the ability to rank experiences by their desirability or importance. Salience is processed through emotion, which I understand as feeling (e.g. "pain", "pleasure") plus evaluation of the feeling as important for flourishing (e.g. "more urgent", "less urgent", "more satisfying", "more joyful"). For example, the joyful feeling I get when eating dark chocolate is more desirable to me than the joyful feeling I get when eating a banana. Therefore, when offered a choice between banana and chocolate, I will opt for the chocolate.

Species that exhibit the three qualities of nociception, subjective awareness, and a sense of salience are sentient: Their members are able to, first, evaluate experiences as more or less desirable and, second, pursue the more desirable states. This means that sentient beings lead lives marked by continuous striving for goals. Unfortunately, in today's world such striving is vulnerable to thwarting by humans. That is the fundamental injustice Justice for Animals seeks to remedy.

What living beings are sentient?

So who precisely is sentient? Pointing to the latest science, Nussbaum says mammals, fish (but not elasmobranch fish such as sharks or stingrays), birds, and probably reptiles exhibit sentience. Plants likely do not (p. 150). Insects are probably not sentient either, because they appear to lack nociception, but honeybees "seem to be an exception to this rule, displaying avoidance learning" (p. 147).

Nussbaum's take on bees - which is very likely focused on the European honeybee apis mellifera - gives me pause. As a backyard beekeeper I know of the vast amount of research that has gone into figuring them out. It is largely driven by economic interest: Honeybees serve as key pollinators to our food supply, and in 2022, they produced $43 million worth of beeswax and $9 billion worth of natural honey worldwide.[2] These economic incentives do not apply to the other insect species that populate our planet, and as a result we know next to nothing about them. So when we label well-studied honeybees as probably sentient but the remaining one million insects as likely not sentient, do we speak from knowledge or rather ignorance?

In fact, I wonder if it is only a matter of time until we recognize other insects as sentient, too. Take the American cockroach. If a decade from now scientists label it sentient, it will not surprise me one bit, as these critters strike me as intelligent, social, striving and very much aware that I am bad for them.

So assume for a moment that insects turn out to be sentient. Would we humans become responsible for enabling their striving, too? That could become very, very difficult.

The Capabilities Approach in practice: living with companion animals

Let's move on to examine two practical applications of Nussbaum's framework by looking at her thoughts on companion animals and on animals we eat.

Companion animals are those animals who live with humans. This includes pets - a term that Nussbaum rejects because it objectifies living beings as toys. But it also includes those animals who have been bred, over centuries, to live with humans on farms: horses, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, chickens and others.

Nussbaum wants us to view companion animals as citizens with responsibilities - for example, the responsibility not to bite humans - and rights. The rights ought to be protected by law and claimed through a designated human partner or ombudsperson, the same way it is currently done for children and grown-ups with cognitive impairments. The human partner would have the right and duty to sue on behalf of the injured, neglected, or otherwise violated animal.

And just in case you wondered: No. The goal is not to give dogs and cats the right to vote (p. 205).

Owners of companion animals have an individual duty to care for their companions. For dog owners, this requires understanding the needs of their breed and meeting them - for example through ample social time and long walks where the dog now and then gets to be in the lead. Care may include killing companion animals, but only when doing so serves them (for example when it is clear that a terminally ill dog is suffering and wants to die - see p. 164).

The practice of breeding for purely aesthetic purposes should be abolished, because it serves only the vanity of the human owner, not the needs of the bred creature.

On the other hand it is acceptable to put animals to work, as long as the work is humane and animals (just like humans) derive satisfaction from it. Oxen, for example, are cattle trained to work as draft animals, and if they are treated well, says Nussbaum, they flourish in their jobs (p. 220).

Dairy cattle are a different story. The large quantities of milk a modern dairy cow produces damage her health, and to keep the flow going, she is forced to give birth once a year, only to have the calf torn from her on the day of delivery. That separation comes at great emotional cost to both mother and child. Nussbaum concludes that dairy cattle live in "a moral horror" (p. 220). I imagine that to do justice to such cows we would have to find alternative sources of protein and wean ourselves off dairy.

The Capabilities Approach in practice: killing non-companion animals

I stated earlier that the Capabilities Approach allows us to kill a companion animal for its own benefit. Meanwhile killing such a creature for the benefit of humans is an injustice. That begs the question: How permissible is it to kill other animals that share our living space but are not companion animals?

I'll look at the idea of a) killing pests and b) killing animals to feed humans.

a) Killing pests: the self-defense principle

There are sentient animals that cause harm to humans. Rats are a case in point, mostly because they transmit diseases (for example the deadly Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome). To these animals, explains Nussbaum, the self-defense principle applies: If we have to choose between our own survival and the flourishing of a sentient creature, it is permissible to choose the former, even though killing the pest means thwarting its striving and thus inflicting an injustice on it (p. 167).

b) Shorten animal lives to feed humans

Is it acceptable to kill a sentient animal in order to eat it?

Let's keep in mind that the overwhelming majority of animals destined for human consumption are born, raised, and killed under factory farming conditions where they do not have the slightest opportunity at a flourishing life. Nussbaum rejects this practice vehemently (p. 165).

With factory farming out of the way, let's shift our focus to animals that do lead a flourishing life. Is it acceptable to kill them for food?

b-1) Killing sentient animals prior to adulthood

There are different philosophical ways of framing the morality of causing such death. The one she prefers is the interruption argument, which says that most deaths "change the life that was lived, and for the worse" (p. 161).[3]

Using the label "adulthood principle," Nussbaum explains that interruption is always a harm when it comes before the animal has reached the stage of adulthood and the modes of functioning that characterize this stage (p. 165 and 166). Under the adulthood principle slaughtering calves and lambs - and probably also male chicks, whom we routinely cull - is thus an injustice.

b-2) Killing sentient animals when they are adult

Once sentient creatures have reached adulthood, interruption through death is only an injustice when it happens to beings that are aware of the passage of time:

"When a life contains a temporal unfolding of which the subject is aware and which the subject values, death can harm it. However, not all creatures have lives like that … and therefore the argument does not establish that death is a harm to all creatures." (p. 161)

She restates this:

"Lives unfold in time, and for a creature highly conscious of time and who lives, as humans typically do, in both the past and the future as well as the present, death can be a harm by interrupting the temporal flow … The Capabilities Approach gives us a way of looking at characteristic activities that supports these judgments, by asking us at all times to consider the creature's whole form of life, including its temporal shape. A focus on maximizing moment-to-moment happiness, by contrast, omits temporally extended projects." (p. 163-164)

Here is how I understand this: If a creature's typical striving entails making long-term plans, curtailing its life is tantamount to a significant thwarting. On the other hand, if the time horizon of plans is very short, there is not significant interruption and hence no significant thwarting.

For my taste this is too vague, for two reasons: First, my understanding is that all sentient beings by definition live a life with a temporal unfolding, simply because time is what permits the formation of memories and thus the development of a subjective viewpoint (and a subjective viewpoint is dimension number two of sentience). If my interpretation is correct, all sentient animals are thwarted if their lives are interrupted.

Second, animal species differ greatly in their life expectancies. That of a mouse is 18 months, whereas that of an elephant is seventy years. How do we compare the temporality of their respective endeavors, and how do we determine at what point we may interrupt them by killing the animal?

b-3) Killing non-sentient animals

Even though the Capabilities Approach applies only to sentient animals, Nussbaum addresses the fate of non-sentient animals, too:

"We do no harm to non-sentient creatures when we kill them, and since they do not feel pain we need not worry too much about the manner, although it is always a good wager to kill painlessly, since we may learn more and decide we were wrong, as we seem to be doing in the case of lobsters." (p. 167)

I wish she had stuck to sentient animals and not spoken about non-sentient beings, for it seems to me that her reasoning is incorrect: A being is sentient if it meets the three criteria of nociception, subjective viewpoint and salience. If an animal has nociception and salience but lacks a subjective viewpoint, it is not sentient. However, since it has nociception, it can still feel pain. I therefore do not understand why Nussbaum equates non-sentience with the absence of pain.[4]

Tragic dilemmas and how to solve them

When discussing the killing of pests, I pitted two important values against each other: The need not to thwart the flourishing of a sentient rat and the need to defend our lives against disease.

Similarly, Nussbaum pits two values against each other when she feeds herself: Even though her Capabilities Approach suggests that fish likely experience harm by being killed prematurely, she eats fish rather than switching to a vegan diet, because to survive, she needs protein, which her body has difficulty extracting from plant sources such as legumes (p. 169).

These two vignettes exemplify tragic dilemmas. They

"are caused by the fact that people, with good reason, cherish plural values, and events out of their control make it impossible to fulfill the moral demands of all." (p. 175)

If a society decides that it wants to be guided by the Capabilities Approach, the amount of unjust thwarting should drop, but due to the existence of tragic dilemmas it would not disappear entirely.

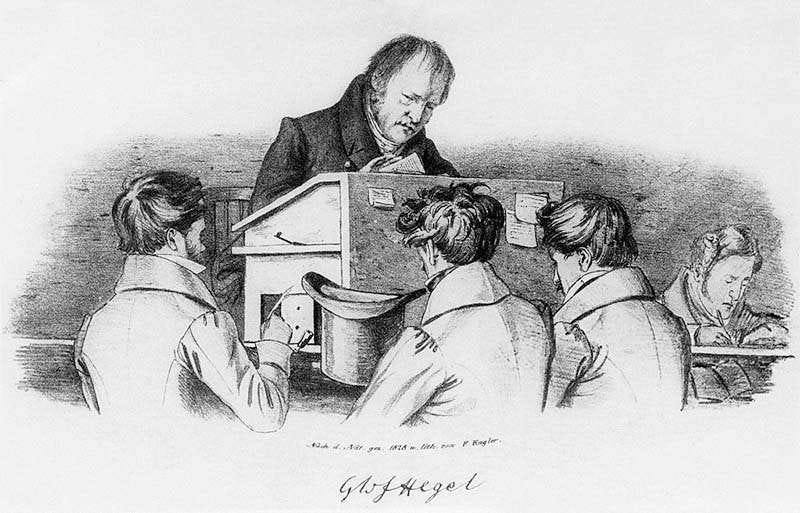

Nussbaum approaches tragic dilemmas with help from the nineteenth-century German philosopher Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel.

"Tragic clashes between two spheres of value, he argued, stimulate the imagination to think ahead and change the world: for it would be better if one could find a way to prevent the tragic choice from arising in the first place. The bad choice is before us, now; but the next time let's try to figure out how to prevent it." (p. 175)

In practice this means being aware of and honest about the clash in values and using one's creativity, as well as that of others, to conceive a future in which the values in question will no longer clash. For example, Nussbaum suggests that a decade from now bacteria-grown vegan meat alternatives might be so affordable and health-promoting that people with a legume intolerance can easily make the switch from fish- to plant-protein.

Can we reduce the tragic dilemma of killing sentient creatures by eating larger animals?

Lab-grown meat ten years down the road sounds good. In the meantime, could we reduce our dilemma by substituting larger animals for smaller creatures? I have the following thought experiment in mind: A cow yields about 600 pounds of meat, while a broiler chicken yields five pounds. It thus takes 120 chickens to produce the same amount of meat we can get from one cow. Assuming that both animals have a sense of time and that killing them would therefore be an injustice, could we minimize the ethical offense by killing one cow, committing a single injustice, instead of slaughtering 120 chickens, which would result in 120 cases of injustice?

Perhaps Nussbaum would object that we cannot compare and rank the importance of lives, especially since, like Kant, she believes that every creature is an end in him- or herself. And perhaps the practice of ranking the value of lives would be as objectionable to her as utilitarians' disposition to rank individual preferences. But as soon as we kill a living being to serve us as food, we are treating it as a means. And considering that we do so at an enormous scale - humanity currently devours 360 million tonnes of meat per year - the question of substitution begs to the answered.

Other tragic dilemmas

Tragic dilemmas occur in many other areas of life, and Justice for Animals discusses several:

Medical experimentation on animals (p. 178-183).

The hunting practices of threatened traditional cultures (p. 185-189).

Larger conflicts over space and resources (p. 189-192).

And of course, if we are responsible for the flourishing of most sentient life on Earth, the dilemma of choosing between predator and prey arises: Should we enable the flourishing of predators, who, through their species nature, curtail the lives of prey? Or should we prioritize the prey and protect it from the predator, thereby thwarting the latter?

Animals in the wild

This last question haunts chapter 10 of the book, which bears the title "The 'Wild' and Human Responsibility." It examines our obligation to manage the relations among animals in unbuilt and uncultivated areas.

Conceding that this chapter may be the most controversial among animal lovers, Martha Nussbaum anticipates two important objections to interfering in wild ecosystems:

Objection 1: Humans don't understand the full complexity of these ecosystems and the webs that connect their inhabitants with one another.

Objection 2: Much human interference in wild ecosystems paternalistically infringes on the life choices of its inhabitants.

Here is her response:

"This discussion … presupposes that there is such a thing in the world as 'wild' Nature: spaces that are not under human control and supervision. It presupposes that it is possible for humans to leave animals alone. That presupposition is false." (p. 228)

The question, then, is how to intervene, exactly. For this, she proposes the following stewardship practices (p. 234-235):

Humans must stop measures that aim at the violation of wild animal life, health, and bodily integrity. Examples are poaching, commercial whaling, or hunting for amusement.

Humans must stop conduct that unintentionally but systematically causes animal death and suffering. An example is bright lighting on urban buildings, which causes migratory birds to crash into lit windows.

Humans must remedy damages to animal habitats that likely have a human origin. An example is protecting the wilderness from the impact of climate change.

We should stop encroaching on wild habitats, so as to leave room for animals.

We must use our knowledge to protect wild animal lives.

We may be under obligation to provide veterinary care.

In my view suggestion number five is the most problematic, because it poses the tragic dilemma of having to choose between predator and prey that I mentioned earlier. Fortunately, Nussbaum is fully aware of how difficult it is to manage relations among untamed animals, and therefore proceeds cautiously: She emphasizes that her conclusions are tentative and concedes that the Capabilities Approach leaves room for different viewpoints (p. 224).

Takeways

The framework that Martha Nussbaum has given us is not air tight. I raised a few questions: First, if large numbers of insect species turn out to be sentient, how will this affect the viability of the Capabilities Approach? How could we make the theory work in the face of very many, very small sentient beings? Second, when it comes to reducing the injustice committed by slaughtering sentient animals, would it work to substitute larger for smaller creatures?

A third question was posed by Nussbaum but left unanswered: When managing relations among animals in the wild, as the Capabilities Approach tells us to do, how do we value the needs of predator compared to those of prey?

The Capabilities Approach tells us that the lives of sentient beings are invaluable. But in practice it runs up against situations, like those of questions two and three, where the impulse to compare the value of sentient lives arises. How does one respond to this urge?

That said, I believe that the Capabilities Approach offers a great opportunity for creativity. Think of it as a mental construction set - a sort of Lego for adults: Nussbaum has given us basic building blocks (wonder, compassion, transition anger, sentience, capabilities, tragic dilemmas), an overarching strategic vision (treating animals with respect), a comparison with other construction sets (the Great Chain of Being and the So-Like-Us approach, utilitarianism, Kantian philosophy), and specific building plans (strategies for approaching companion animals, zoos, pests, wild areas). Now it is up to us, her readers, to expand, strengthen, and deepen the Capabilities Approach into a structure that can carry the very heavy load it is meant to shoulder.

I would love to see Justice for Animals spawn new research programs that integrate nature-focused philosophy and science and that use the Capabilities Approach as their cornerstone. I would also love to see its views of justice put into practice, starting with the phase-out of the unbearably cruel factory farm system. It isn't clear to me how we will do it, or when. But Justice for Animals has beautifully shown that it must happen.

For me personally, the volume has reinforced just how important wonder is to improving the dismal state of human-animal relations. Too few of us get the opportunity to interact with wildlife, by holding a toad or by watching a new butterfly crawl out of its chrysalis and then pump hemolymph (insect blood) from its swollen abdomen into the crumpled wings, slowly inflating them into a glorious display of color. If wonder is at the root of animal-forward social change, then we must create many more opportunities for it.

Let's return to the vignette of the local fair that I presented at the start of this essay. The Audubon Society rescues injured birds. Some of them cannot be released into the wild because they have lost the ability to live on their own. With training and the right personality they can become "avian ambassadors." That means that from the safety of their perch - usually the arm of a trusted human handler - they allow persons to approach them. Such encounters last on average five minutes, and for humans these can be profoundly meaningful. So much so, perhaps, that they engender the very wonder, compassion and desire for betterment that are essential to justice for animals.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2023. Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Footnotes

[1]: The formal term for factory farms is concentrated animal feeding operations. This estimate of ten billion animals is provided, for 2017, by Our World In Data. I infer that subsequent years produced, roughly, the same number.

[2]: The data is provided by FAOSTAT. Search for "beeswax" and "natural honey" worldwide in 2022.

[3]: She likes the interruption argument because just like the Capabilities Approach it looks at life as a time-constrained potential for pursuing projects.

[4]: She says pain is a feeling, not a (more complex) emotion. For more on the distinction between feelings and emotions see p. 131-137.